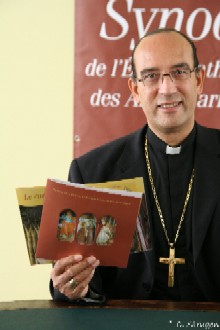

With 710,000 baptized Catholics in the Alpes-Maritimes department, the Bishop of Nice may not have “divisions” as Stalin would have asked about the Pope, but he has troops that gather nearly two-thirds of the population of the Alpes-Maritimes. Suffice it to say, from the perspective of the municipal elections, his voice “enlightened by the Gospel” will have some influence. But this HEC graduate who was preparing for an international career in business before being “flipped like a pancake by illumination” knows how to talk about God with humanity without making him the “incomparable man” of Ernest Renan. Initiator of the convocation of a Synod in April 2007 to respond to the inner questioning of his faithful, Archbishop Louis Sankalé prefers to insist on the “Trinitarian dialogue” rather than the Vatican dogmas with which, gently, he makes a little different music: ordination of married men, openness to other religions, the place of man in society, no question seems taboo for this man of the Church but especially of the field. “We’re not on another planet,” he repeated several times.

With 710,000 baptized Catholics in the Alpes-Maritimes department, the Bishop of Nice may not have “divisions” as Stalin would have asked about the Pope, but he has troops that gather nearly two-thirds of the population of the Alpes-Maritimes. Suffice it to say, from the perspective of the municipal elections, his voice “enlightened by the Gospel” will have some influence. But this HEC graduate who was preparing for an international career in business before being “flipped like a pancake by illumination” knows how to talk about God with humanity without making him the “incomparable man” of Ernest Renan. Initiator of the convocation of a Synod in April 2007 to respond to the inner questioning of his faithful, Archbishop Louis Sankalé prefers to insist on the “Trinitarian dialogue” rather than the Vatican dogmas with which, gently, he makes a little different music: ordination of married men, openness to other religions, the place of man in society, no question seems taboo for this man of the Church but especially of the field. “We’re not on another planet,” he repeated several times.

Nice-Premium: It’s been four years, Archbishop, since you’ve been exercising in the Diocese of Nice. What is your feeling about the community of Nice’s faithful?

NP: Reorganization due to a lack of vocation?

Archbishop Sankalé: Yes, it can be seen that way. There was certainly a decrease in the number of priests leading to their distribution in a way that served the maximum number of places of worship. But this phenomenon of parish regroupment was general in France for about thirty years. There were issues with priests, laity, and also the fact that certain areas of our department, notably the Upper Country, are less populated than before. Where is the time when there was a parish priest per steeple in these municipalities, meaning a vibrant community around: you were born, grew up, got married, and ended your days there, and it was a place of life. Today, some of these places are depopulated but retain a vibrant activity during the summer. I love visiting these areas and seeing on the ground the work of priests appointed there. We have moved to 45 parishes, and people say, “we have changed the number of train cars, but where are we going?” In response to this persistently asked question, I said upon my arrival that I had three priorities: youth, solidarity, and families. This doesn’t mean the rest is less important, but I wanted to highlight three priority areas. That was not enough. One thing is for the Bishop to say something important and engage the faithful in a work; another is for the faithful to feel part of these orientations. For that, I called a Synod, a work of the entire Church, all baptized Catholics of the Alpes-Maritimes, to jointly define orientations. That is what we have been working on since last April. It should last two years until Pentecost 2009, when I plan to promulgate the jointly decided orientations.

<img23466|left>

NP: Does this pastoral questioning of Nice’s Christians correspond, in your view, to that of European Catholics who show a decrease in affiliation with monotheistic religions and an increase in the need to refer to beliefs?

Archbishop Sankalé: It is indeed something we find. We are not on another planet and are part of this society, and in many respects, we feel the need, I almost said, to evangelize people who have been baptized. We need to clarify, to refine what it means to be a Christian. In the broad panorama of religious life, all possibilities are available for those seeking transcendence to join this or that group. Everyone makes their choice, and it doesn’t spare the baptized and Catholics of our department. We must simply answer the question, “What does it mean to be Christian? What opportunity does it provide and what duties does it create?”

NP: In this vein, a recent survey by the newspaper “La Croix” states that for more than 60% of the French and 63% of practicing Catholics “all religions are equal.” What comments do these figures prompt from you?

Archbishop Sankalé: I find it interesting that the question was posed to Catholics, and it would be interesting to compare these numbers with those from a survey of the entire population. Dialogue is constitutive of the Christian faith. For Christians, God is dialogue, so to speak. He is one, we believe in the uniqueness of God, in one God, but this unique God possesses within Himself a life, a love that is exchange and self-transcendence. He is therefore life circulation and dialogue. There is an incessant dialogue between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in Christian faith, making us believe in Him and Jesus Christ who reveals Him to us. We are introduced into the dialogue of the Son with his Father and become actors in this dialogue ourselves. We turn to our brothers to engage in dialogue with them. There is something constitutive of Christian faith leading me to say that dialogue among Christians is not an option; it is not something optional reserved for those with this sensitivity. Dialogue, especially inter-religious dialogue, must be a permanent appeal for the disciple of Jesus, constantly invited to enter dialogue with God and his brothers. This survey does not surprise me much. It reveals this desire to engage in dialogue with, of course, the risk of mixing everything and believing that all religions are equal. Many may think so, and that is their right. I prefer to imagine they understood the question well. But have they understood that one can save oneself, that one can be saved, reach the happiness God wants for us by paths other than the Christian faith? Perhaps this is what those who say all religions are equal understood, and I would parallel it with the statement heard not long ago, saying “outside the Church there is no salvation.” The time has ended when we said “outside the Church there is no salvation.” To say that all religions are equal is a shortcut I do not endorse. All religions are respectable. I would say more precisely: all believers are respectable. The heart of the believer is respectable. One can believe differently and not consider oneself enemies. One can believe differently and not look at each other askance. Believing differently does not make us distrustful of others. I would say in a word that may resemble a formula but means a lot to me: what we seek is not to be tolerant but to be dialoguing.

NP: Does the quest of the faithful not correspond to a loss of the “I” in search of the “we,” to use Jean-Claude Guillebaud’s expression, and is the Church, in calling for this dialogue itself, not going back on this notion of individualism for which it was at the origin?

Archbishop Sankalé: Indeed, the “I” as a personal subject is related to the Christian tradition and everything conveyed by biblical revelation and the thought of the earliest Christian authors. I am willing to believe that we have highlighted this “I” to the point of absolutizing it. We have made it an absolute. Absolute, meaning without anything contrary to what this relational being that is God and what He wants to make of us. God is not an absolute. God is relation. He is in Himself. He does not cut Himself off from this other Himself that He engenders and to which He gives birth by producing the third that is the Holy Spirit. In God, there is no refusal of relation, and when He associates us with the knowledge of His Being, He makes us relational beings as well. The “I” is relative. I am not saying it is secondary, but it means that by making it an absolute, we isolate it. We are right to say that “no man is an island.” Perhaps we should see if the word “absolute” is not etymologically linked to isolation? I am not afraid to say that we have to learn relativity. Let us not make the “I” an absolute. We are relative to others; we cannot live and love without being relative to someone else. History, from this point of view, has taught us to turn our backs on all fanaticism, intolerance, things the Church was not immune to either.

NP: What is your theological opinion on the line followed by Benedict XVI and on the dialogue with other religions? Isn’t there some sort of retreat from the openness achieved by John Paul II, and doesn’t interreligious dialogue seem to have stalled?

Archbishop Sankalé: No. I believe we are still in the dynamic of the Second Vatican Council, inviting Catholics not to be afraid of knowing and being known to other believers, whether they are Christians, Jews, or Muslims, with religion or even without religion. This dynamic is not called into question and continues to fuel interreligious dialogue. That there is a change in style due to a change in pontificate is normal and is due to the actions of each pope. John Paul II had notably distinguished himself by inviting all religious leaders on the planet to Assisi in October 1986 for a joint approach to peace, affirming together that one could live on the same planet, believe differently, and not wage war. This attitude accompanied his entire pontificate, notably during the “Great Jubilee,” where he did not hesitate to make this act, quasi-prophetic in my eyes, of repentance which has not always been well understood. But which for me meant simply, “Listen, if none take the first step towards others, if everyone confines themselves to their ‘I am right,’ then we will not get out.” This act of repentance, again not always well understood, has inspired some here and there. There are states or leaders who have entered into this dynamic. Benedict XVI arrived. Obviously, his Regensburg speech where he cited the Qur’an and Muslim tradition was a source of misunderstanding and needed to be remedied as best as we could.

NP: What about the pontifical discourse on the primacy of truth issued by the Church of Rome?

Archbishop Sankalé: Indeed, this statement, which is a reminder, is in a tone that is somewhat new and was perceived by some as an act, how to say, of hardening.

NP: Like the “Motu Proprio” of June 15, 2007, on the Latin Mass?

Archbishop Sankalé: When reading the Pope, the “Motu Proprio” was intended as a means to achieve unity with those who had distanced themselves from the liturgy. It was an act towards unity in their direction. Varying interpretations. In this regard, I am returning from the Conference of Bishops of France in November and, quite generally, there are not as many requests as one might have expected, and those that are made receive responses from bishops. With our priests, we have the means to respond. It is not necessary to bring in other priests from Epône or the Mont Pasteur to meet these requests.

NP: Cardinal Etchegaray, vice-Dean of the Vatican’s Sacred College, recently stated that the question of the ordination of married men could “arise.” What do you think?

Archbishop Sankalé: I know Cardinal Etchegaray well since he ordained me as a priest in Marseille in 1976. I am not at all surprised to hear him say that, and I share this view. It’s a question that can arise and has already been posed. I am not even talking about the primitive church but about the aggregation to the Catholic Church of married priests coming from Anglicanism. The question is already posed. It does not have an answer excluding those who would be married. So, there are currently married Catholic priests, not to mention all the Eastern churches. The non-religious Maronite clergy is a married clergy. It is a question that we have the duty to raise within the dynamics of what the Council asks us, namely, a missionary audacity that draws from apostolic sources.

NP: Rome gives the feeling of not really wanting to pose the question.

Archbishop Sankalé: Yes

NP: That doesn’t surprise you, either.

Archbishop Sankalé: It is easier to maneuver a dinghy from the Port of Nice than the large boat heading towards Corsica. Rome is a big boat. They can try to maneuver but it involves so many things…

NP: A conference on “the future of Eastern Christians” has just been held in Paris. Do you think in some regions, particularly in the Arab-Muslim world, Christians are more threatened than elsewhere?

Archbishop Sankalé: I don’t like much comparison in this case. To say they are, yes. To say they are more than elsewhere, I would say…see. Because there are threats of painless absorption into comfortable materialism that are no less deadly than threats of open persecution. I don’t know Lebanon. I only know the Holy Land where I have encountered many communities. I have felt, through these contacts, the disarray and at the same time the hope of these Christians. That there is a real issue of physical presence that resists the temptation of exile and sometimes the necessity of exile is undeniable. The Catholic Palestinian from Bethlehem who was our guide during my last trip to the Holy Land spoke to us about his three children who are grown and have made their lives elsewhere. He observed this with some regret, some sadness, and at the same time with hope that made him say nevertheless: “not everything is lost.” And what made him say this was that the fate of some is tied to the fate of others. I avoid saying Israel because it doesn’t please some, nor Palestine because it doesn’t please others, but what strikes is this weighty shroud on everyone, it is truly something harsh, and at the same time, the fact that it is not over…even if we do not see very well how we will manage to get out of it. We think we will get out together or we will remain in it together.

NP: Driven by the two other monotheisms, doesn’t Christianity question the strict separation, stated by the Gospels, between the temporal and the spiritual? Aren’t there more and more Church interferences in political and social issues, in societal debates?

Archbishop Sankalé: I would say yes, the Church intervenes, expresses itself on issues affecting societal life. I do not feel it does so more than before. If you look at a bit of Church history, you’ll see it has been much more involved in temporal life. We are no longer in this alliance of the sword and the aspergillum. But that the Gospel is a leaven of renewal, human progress, uplifting, liberation, or hope for man is its vocation. Do Christians always do it well? Sometimes, I mention the words of the singer Gérard Lenorman: “It is not God I blame, but those who spoke to me about Him.” I believe the Gospel remains a leaven of humanity for our society. What puzzles me the most is not that society is dechristianized, but that in dechristianizing, it dehumanizes. It is there that we want to have a prophetic word and the assurance of having a treasure we want to share.

NP: In conclusion, Archbishop, a simple question: Spiritually, the right candidate for the Mayor of Nice?

Archbishop Sankalé: I will refrain from answering. That doesn’t mean I will refrain from voting. In my position, I cannot indicate a voting orientation except to say that in the light of the Gospel, it’s about being before one’s conscience, responsible for the choice one makes for the future of Nice society and its communes. I cannot say more, but I can tell you that I will vote. I do not abstain regardless of the nature of the vote, national, departmental, communal. I do not have to vote in the labor union elections but if I did, I would. Because it seems important to me. The only duty is to invite people to do the same. Abstention is sometimes advocated as a political act, but it must not be a resignation. We are not, once again, on another planet. We are in a society that is ours. I invite everyone to stand under the light of the Gospel to make a conscientious choice.