Nice Premium: How did you approach your character?

Jean-Claude Adelin: I went to Cuba a month before filming. I practically lived there for 30 days with the director. We talked a lot about young black people, immigration… I read a lot of documentation, history books. I also read the Code Noir. If you haven’t read it, I recommend it. It’s the most horrible book after Mein Kampf. It contains 60 articles of law written by Colbert. It was the French law of the time that authorized slavery and explained to whites how they should manage slaves, meaning as beasts and as instruments of labor. It’s very powerful to read. It moved me. I posted the Code Noir in my room and also a picture of all the characters from “Tropiques Amers”. I lived like that for a month.

Jean-Claude Adelin: I went to Cuba a month before filming. I practically lived there for 30 days with the director. We talked a lot about young black people, immigration… I read a lot of documentation, history books. I also read the Code Noir. If you haven’t read it, I recommend it. It’s the most horrible book after Mein Kampf. It contains 60 articles of law written by Colbert. It was the French law of the time that authorized slavery and explained to whites how they should manage slaves, meaning as beasts and as instruments of labor. It’s very powerful to read. It moved me. I posted the Code Noir in my room and also a picture of all the characters from “Tropiques Amers”. I lived like that for a month.

N-P: Was it to make an impression on you?

J-C A.: Yes, plus we were in Cuba. It was an extraordinary opportunity. In Cuba, there is a lot of racism. There is a terrible hierarchy: the State and the Men who are not quite treated as men or women. There was terrible segregation. It was the black people who swept, the black people who brought you food, not the white people. And in production, it was only white people, no black people. And between white and black, you have all the shades of color. From light to darker brown, there is also racism within. It was very conducive ground for my character.

N-P: A character very different from Jean-Claude Adelin.

J-C. A.: What do you think?

N-P: Yes.

J-C A.: Yes, very different. It’s nothing alike. I think the opposite is what did it. I find it to be the most beautiful thing I’ve done. When I read the script, it takes your breath away. I didn’t want to do it anymore. I was scared. I would never be able to do it. I couldn’t pretend, especially for the sake of memory and respect for the people who lived these stories. Our actors’ ancestors, who were with us, lived through that. The director helped me a lot because he’s Guadeloupean, and he’s a man with a huge heart. The violence I felt, I channeled into the character because I had a kind of very intense rage and despair. No more of this, ever. The character I portray is extremely violent.

N-P: Violent, but endearing.

J-C A.: Yes, he’s endearing. It’s done very intelligently. He is not black-and-white. They’re not all horrible. They’re not all vile and despicable. There were also people who had a heart. And he was in a structure. He was there to work; it was a factory. There were workers producing sugar. It was the French economic system that was in place. It’s purely a question of money. Why were there slaves? Initially, they were whites: orphans, convicts, adventurers… they had three-year contracts. But the problem was that whites couldn’t last three years in those conditions (heat, malnutrition…). So, they had to find something else. They went to get Africans because they were used to the sun.

J-C A.: Yes, he’s endearing. It’s done very intelligently. He is not black-and-white. They’re not all horrible. They’re not all vile and despicable. There were also people who had a heart. And he was in a structure. He was there to work; it was a factory. There were workers producing sugar. It was the French economic system that was in place. It’s purely a question of money. Why were there slaves? Initially, they were whites: orphans, convicts, adventurers… they had three-year contracts. But the problem was that whites couldn’t last three years in those conditions (heat, malnutrition…). So, they had to find something else. They went to get Africans because they were used to the sun.

N-P: This film is rich in emotion. It traces a part of a nearly unknown history because if you look at a school history book, only a small paragraph references it. In school, we just learn the date of the abolition of slavery.

J-C A.: Yes… Three, four dates… Yet, it’s important to say. It’s important for people to see this film, to become aware of it. They have to know. There should no longer be any unspoken truths because once there are no more unspoken truths, we can move on to other things.

I want this film to be seen; it’s a necessity.

N-P: “Tropiques Amers” is a film to be shown in schools.

J-C A.: Exactly. In fact, we went to the Paris suburbs to the DDASS to discuss with children who had seen the series. I will do it at every opportunity.

N-P: How do you come out of this character?

J-C A.: You don’t. Besides, I don’t want to; you shouldn’t come out of it. You have to keep some. The characters you meet, especially those that impose themselves and stir so much in me, it would be a shame to leave them. It brought me so much. I don’t see life the way I used to. It’s amazing to say that. Now, I no longer want to be silent. Before, I didn’t dare. But on the contrary, you have to speak; it’s important. If you don’t speak, it continues.

N-P: Jean-Claude Adelin was a hairdresser before.

J-C A.: Yes.

N-P: How did he become an actor?

J-C A.: A series of opportunities. I had a difficult father, but he was passionate about cinema. The only happiness I had with him was in front of the TV, watching Westerns and American, French crime films from the 40s-50s-60s. At first, I worked in construction, where I was freezing, drilling holes in walls to lay electric cables. Then, I had a fiancée who was a hairdresser. She earned more than me; she had tips, and it’s an environment with beautiful girls, so at 16, you quickly change orientation. I left construction. One day, I did a hairdressing replacement on a film. And there you go, it landed on me.

N-P: Actor but also director.

J-C A.: Yes, I directed two short films and a documentary. I’m preparing a feature film about detainees seen from the other side, from the  family’s perspective. I’m writing with a former detainee who served 18 years. I was part of an association, unfortunately now ended, of prisoners’ wives. It’s not easy for them; they’re also prisoners. The detainee is never geographically close to their family; their prison is at the other end of France. It breaks the mental state of both the detainees and the family by separating them. There’s no possible tenderness during visitation. If there is, they are punished, while the law’s punishment is meant to protect society from this person who committed a crime, but there’s no law article stating that the prisoner should be deprived of affection and closeness. De Gaulle said: “I would never lift the lid off France’s prisons”; the trash of France, no one dares to.

family’s perspective. I’m writing with a former detainee who served 18 years. I was part of an association, unfortunately now ended, of prisoners’ wives. It’s not easy for them; they’re also prisoners. The detainee is never geographically close to their family; their prison is at the other end of France. It breaks the mental state of both the detainees and the family by separating them. There’s no possible tenderness during visitation. If there is, they are punished, while the law’s punishment is meant to protect society from this person who committed a crime, but there’s no law article stating that the prisoner should be deprived of affection and closeness. De Gaulle said: “I would never lift the lid off France’s prisons”; the trash of France, no one dares to.

There’s a lot to do; I don’t think it’s hopeless. Young generations need to be aware so they can create a better world.

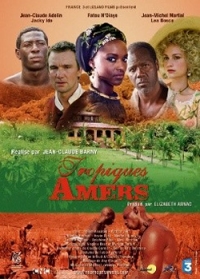

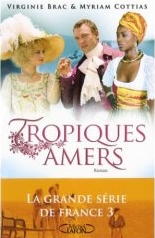

INFO:

If you missed the broadcast on France 3, the series “Tropiques Amers” is available on DVD.