An exhibition that for the first time reveals the fruitful relationship of the painter with the world of the 7th Art can be seen at the F. Léger Museum until September 19 in Biot.

A cinephile, creator of sets, posters, theorist, director, producer, or even actor, all facets of the artist are showcased in this venue. During World War I in 1916, while on leave with his friend Guillaume Apollinaire, he discovered Chaplin’s films, a true passion for him. From 1919, the cinematic influence can be felt in the painter’s work. He believed in the future of Cinema: “Cinema personalizes. It frames the fragment, and it’s a new realism whose consequences can be incalculable.” Léger almost abandoned painting for Cinema. How could painting “bring movement to life” as Cinema does?

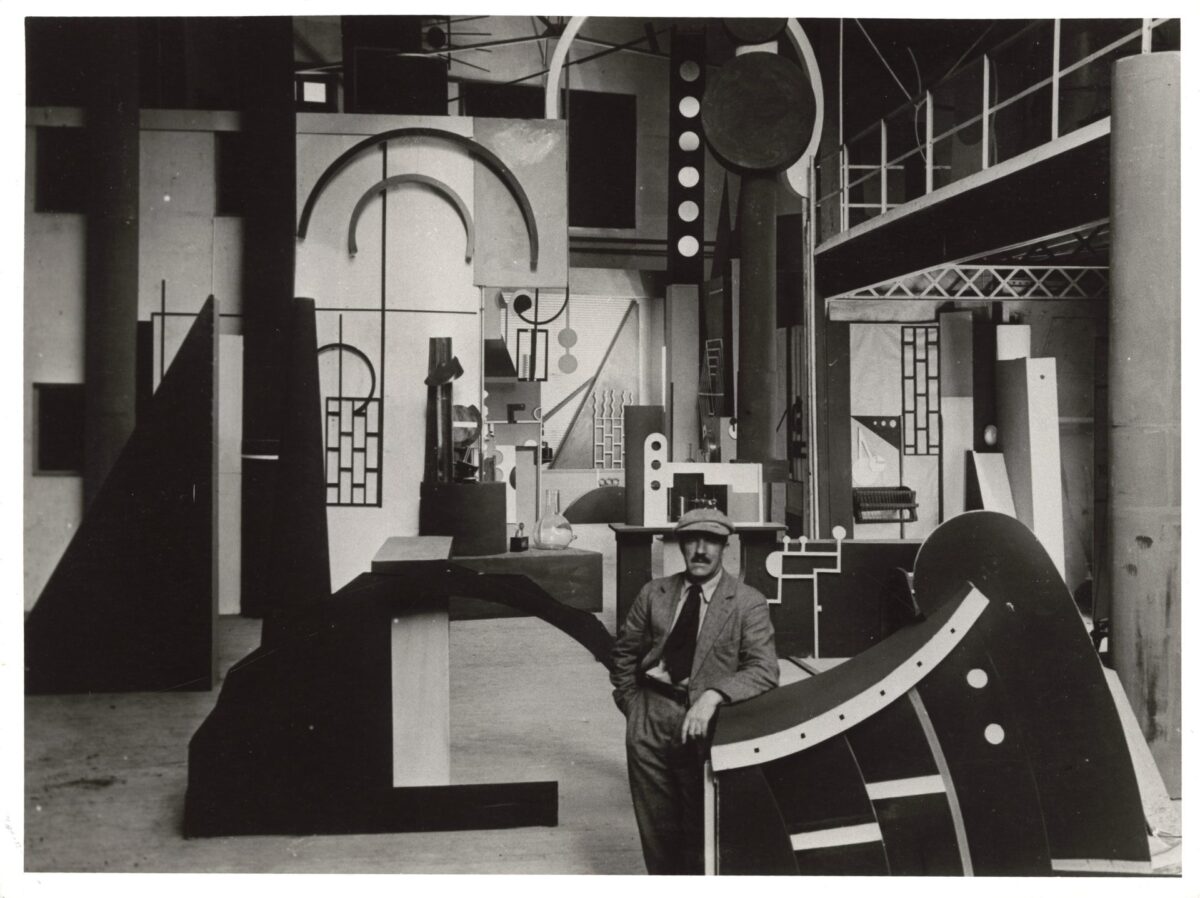

The exhibition offers, in its large halls, the full range of expressions of the passionate artist. We immerse ourselves in excerpts from great works of the 7th Art such as “Children of Paradise” by Carné or “The Wheel” by Abel Gance. The first making-of in Cinema, produced by Blaise Cendrars, then an assistant director to Abel Gance, is on display. The exhibition also showcases the projects of opening credits and sets for the futuristic laboratory in Marcel L’Herbier’s film “L’inhumaine,” one of the oldest science fiction films. We are in the 1920s, and this film brings together architects, furniture creators, and costume designers like Robert Mallet-Stevens, Pierre Chareau, or Paul Poiret. In the 1930s, surrealist aesthetics greatly influenced Léger, an aesthetic particularly characterizing the film “Dreams That Money Can Buy,” released in 1947, directed by painter and filmmaker Hans Richter with the participation of Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Alexander Calder. Thanks to the loans from the Cinémathèque and the Centre Pompidou, from galleries and private individuals, it’s possible to explore everything related to Cinema in the painter’s work in greater depth, including his paintings when they reference films he had seen. Nothing escaped him, from Keaton to John Ford’s westerns and Disney. Particularly striking is his gouache on paper depicting a stylized Charlot from almost geometric shapes, a project for an illustration for a brochure intended for the Cannes Festival in 1949. Léger was struck by Charlot’s jerky gestures moving to the rhythm of the music. Also, the accessories: cane and bowler hat are kinetic objects in their own right. He was moved by the Poetry, the humanism of the melancholic clown. The social impact of “Modern Times” through the mechanization of bodies, the Society crushing the poorest under the weight of assembly line work born from Fordism interested Léger. The aesthetics of the machine is at the heart of his work’s evolution.

Finally, not to be missed in the exhibition is the installation of a mechanical orchestra by Austrian Winfried Ritsch in 2019, automatically unfolding the American Georges Antheil’s score originally for mechanical pianos and other period instruments (xylophones, percussions, but also airplane propeller noises and various bells) meant to accompany Léger’s experimental film “Ballet mécanique” from 1924, a project in collaboration mainly with Dudley Murphy and Man Ray: a parade of frenetic images (objects, female bodies, and geometric shapes), a film starring Kiki de Montparnasse, model and muse of great artists in the 1920s and 30s. Ultimately, the two works were not synchronized. This orchestra plays fully automatically through computer robots.

This exhibition, organized by the National Museums of the 20th century of the Alpes-Maritimes and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux – Grand Palais, is on display until September 19. Exhibition curators: Anne Dopffer and Julie Guttierez. The mechanical ensemble can be heard and seen until November 13.