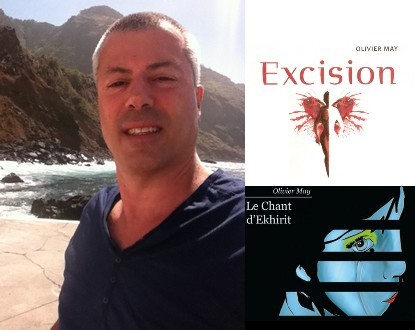

The author of the novels already reviewed on our site, The Song of Ekhirit and Excision, has granted us an interview. A meeting with an author who is not afraid to tackle sensitive themes.

Olivier May is Swiss, born in 1957 in Geneva, and during adolescence, he developed a pronounced taste for imaginative literature that would never leave him.

After studying prehistoric anthropology and history, he participated in an archaeological research program on the early civilizations of the Alps while teaching at a secondary school.

Today, he is a dean at a Geneva college and has published five speculative fiction novels as well as several short stories. In 2013, his first illustrated prehistoric novel will be released by Flammarion Youth Editions.

Nice Premium: How did you come to write a novel about excision, Islam, and the fight for the freedom of Muslim women?

Olivier May: Through encounters. I became aware [of the reality of excision] through contact with students from Somali refugee families. I gathered confidences, and I could speak about it. The courage of these young girls moved me.

When the idea of a novel about terrorism came to me, its connection to the theme of excision was an obvious choice for me, as were the Somali origins of my heroine. I write speculative fiction, a type of science fiction centered around sociological and political anticipation against a backdrop of technological advancements. My heroine would thus be named Aayan and would fight against fundamentalism, archaism, and for the dignity of Muslim women and their integration into modernity, all while not denying her origins.

I tried to avoid stereotypes in the writing as well as political correctness that denies the problems posed by some environments.

In my work as a dean and teacher, I face numerous tricky situations that highlight the status of young girls in some fundamentalist circles. I should specify that this doesn’t only concern Islam but that Muslim girls are overrepresented.

In Switzerland, the veil is accepted in public schools. I’m referring, of course, to a scarf while the burka or niqab covering the face are not tolerated! This also means a veiled girl doesn’t go unnoticed because the vast majority of girls with Muslim traditions don’t wear the veil.

Muslims in Switzerland are well integrated indeed. Eight out of ten are originally from the Balkans and are not particularly devout. If you go to a Bosnian party, for instance, there’ll be alcohol. Moreover, Switzerland doesn’t have a colonial past and has a long history of religious tolerance and an old secularism. To better understand their reality, I read the Quran and some hadiths. I found texts very dated, written in a late antiquity context that comes through in every verse. This message appeared primarily to me as a catalog of prohibitions and exhortations to adopt a highly normative social behavior. To me, it’s the religion closest to true monotheism.

Sometimes it abolishes, sometimes it reinforces the oldest customs. And, of course, there are clear calls for murdering infidels, which is “perfectly normal” in a warrior society of the sixth century.

Excision isn’t mentioned because it’s a pre-Islamic tribal custom that can also affect Christian Copts or animists. However, over ninety-five percent of excision cases take place in a fundamentalist Islamist context.

N P: Excision is a very female-sensitive theme; how did you manage to address this side of things, which is also well rendered?

O. M.: I’m very pleased with your question and that, as a man, you found my treatment of this intimate theme well-executed.

I realized through my readings that several specialists in reconstructive surgery were men. That men took care of these women, took risks. Tens of millions suffer from excision, live mutilated in our contemporary world; let us not forget that.

I wanted to maintain the detachment of an external narrator; I couldn’t imagine speaking in the first person and putting myself in Aayan’s shoes. Moreover, David’s loving perspective, his admiration for her tragic beauty and struggle, was essential. The view of Imam Djellul too.

Figures of men who help to mend, who make resilience possible, although Khadija and Leïla are also important models.

I chose to go to the nerve center of the problem. Excision is sexual mutilation; sex is at the heart of this practice, which tends, however, to eradicate it. Female sexuality, the woman’s sexuality, is at stake. I hope I chose the right angle to approach this very sensitive aspect of the theme and the narrative.

N P: How did you document yourself before writing, through encounters, readings?

O. M.: After some preliminary readings, I constructed the plot, especially the mysterious interchapters in italics, sketched the characters, and found the ending. I then returned to my initial documentation and notes.

I read a lot on the subject but no fiction. They are too rare, by the way. Taboo? I read testimonies, reports, interviews with people directly concerned (I don’t like the term victims; they are too brave for that), or NGO leaders fighting against these practices. I couldn’t meet an excisor, but I read their testimonies. I would have wanted to ask them a simple question: how can a woman perpetuate this barbarism in the name of patriarchal customs? I tried to answer it by reading their testimonies about their role in this chain of misery.

N P: What was your feeling after that?

O. M.: My current feeling is one of urgency. A reader contacted me, and following our meeting in a café, I decided to act at my level. I sponsor a girl by making a monthly donation to her NGO that fights against excision in a very pragmatic way. The deal is this: my contribution helps cover the schooling and board of this young person. I will follow her from afar until she finishes her studies. With my wife, we hope to meet her. She comes from an African animist tribe. I buy her integrity from her parents, who also receive aid. As one of my colleagues says, I buy her parents her right to education and to keep her clitoris.

It’s frightening. But it’s also a hope for a break for all the girls benefiting from this courageous program.

Excision is absolute evil. It’s beyond religion, even if those who inflict it try to link it to that. Excision must be fought against, and excised women must be helped to reclaim their femininity. We are constantly reminded to respect others’ “cultures” and are often invited to relativize our values.

I don’t agree with this angelism and permanent relativism. In all cultures, there have been or still are absolute horrors to combat with the utmost energy. Otherwise, we slaughter baby seals in the Arctic, [or] allow cutting off a thief’s hand. Then let’s reintroduce the Inquisition’s bonfires; it was our “culture”; human sacrifices on Aztec pyramids were the core of their “culture”…

N P: Do you think this subject is well-addressed in France? The fact that you live in Switzerland offers an external perspective…

O. M: The subject might be easier to address in Switzerland because our country doesn’t have a colonial past to its discredit. [Just like in Switzerland] the right to a referendum allows for debates to be initiated and decided by citizens without going through politicians. We then accept the majority decision! A matter of political culture. Thus, the people refused the construction of minarets on mosques; it’s a clear signal to the authorities to set limits on religion in public space.

Personally, I’m okay with accepting any religious expression in a democratic legal framework, but provided it’s confined to the private sphere. I believe excision is one of those taboo subjects where naming things bluntly is avoided for fear of offending (ironic!). It’s absolute barbarity, period.

On issues concerning Islam, France seems caught between the angelic complacency of the republican left and the sometimes hateful identity rhetoric of the right, and excision is then assimilated to an “Islamic” trait.

N P: Between Excision and The Song of Ekhirit, you are not afraid to tackle sensitive and delicate themes, where do these choices come from? a desire to reveal the dark sides of Man?

O. M.: Yes, these two novels and the first three deal with the darker side of our species and feelings like resilience or the desire to exact justice oneself. I purposely choose delicate themes restrained by the political correctness of our time. Excision and pedophilia, they are bad; they are THE embodied evil, and the people who practice them do evil and must be fought without compromise.

The idea that pedophiles are sometimes former abuse victims themselves and that mutilations are “cultural” paralyzes our judgment and shows they have no excuse by following my characters to the end of their logic.

This darker side may be easier to handle for me, someone jovial, generally happy, and very positive in life. A questioning of these deviations that are so far from my life and being, perhaps…

N P: Are you working on a new project?

O. M.: Since Excision, I have three novels and a collection of short stories in the correction phase or about to be published. Two prehistoric novels with fantasy elements, a sci-fi time travel novel around Rousseau’s theses on the noble savage, and a collection of science fiction short stories!