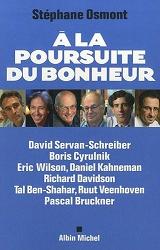

The need for immediacy among our contemporaries is well-known. The pursuit of happiness is no exception: people want to be happy right here and now! Some clever folks have realized the full potential of this vein: launching exceptional “ecstasy kits” on the market, naturally for a price. It’s somewhat this shopping gallery that Stéphane Osmont invites us to explore in his book “In Pursuit of Happiness,” published by Éditions Albin Michel. The author invites us to meet — sometimes a bit fleetingly as time is of the essence — the designers and “manufacturers” of well-being: first discovery, the species is anything but endangered. Spread across the vast world, it has at least allowed this former ENA student to travel from the United States to Denmark, passing through Israel and France. A budget far exceeding that of a psychoanalysis.

He begins by conversing with psychiatrist and “authentic happiness expert” David Servan-Schreiber, who prepares an “anti-cancer meal based on Omega 3” for him, and discusses with him the dangers of “solitude,” the “links between happiness and professional activity,” and the benefits of “breath control.” Not really convinced, our seeker flies to Tel Aviv, where he places much hope in a discussion with Tal Ben-Shahar, a professor of “positive psychology” at Harvard University, where this “science” has been taught for ten years. “Becoming aware of the value of people and things around us,” “making life a matter of journeys more than destinations,” are as many exercises of thought that the author ruefully admits had little effect on him. He then tries a more biological approach, allowing himself to be “implanted with several dozen electrodes on his skull” to satisfy the research conducted by the American neurobiologist Richard Davidson, famous for “photographing” the most intimate emotions. Before speaking with his French colleague, neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik, who finally informs him that it would not be desirable to invent a machine to create happiness because “sensations of happiness and sensations of misfortune are organically coupled in brain areas.” In passing, we learn from the specialist that “early relationships of the individual to life” produce, as in Israel, “the best students in the world,” and that it is also “preferable to live in Scandinavian countries,” where, as in Finland, only 1% of children are illiterate compared to 14% in France. After a quick trip to Ringkobing, a small town in Jutland on the west coast of Denmark, reputed to be the “happiest town in the world,” where he gathers insights from researcher Ruut Veenhoven, founder of the “Journal of Happiness Studies,” Stéphane Osmont joins economist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman in New York, awarded for uncovering the psychological dimension of economic decisions.

He begins by conversing with psychiatrist and “authentic happiness expert” David Servan-Schreiber, who prepares an “anti-cancer meal based on Omega 3” for him, and discusses with him the dangers of “solitude,” the “links between happiness and professional activity,” and the benefits of “breath control.” Not really convinced, our seeker flies to Tel Aviv, where he places much hope in a discussion with Tal Ben-Shahar, a professor of “positive psychology” at Harvard University, where this “science” has been taught for ten years. “Becoming aware of the value of people and things around us,” “making life a matter of journeys more than destinations,” are as many exercises of thought that the author ruefully admits had little effect on him. He then tries a more biological approach, allowing himself to be “implanted with several dozen electrodes on his skull” to satisfy the research conducted by the American neurobiologist Richard Davidson, famous for “photographing” the most intimate emotions. Before speaking with his French colleague, neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik, who finally informs him that it would not be desirable to invent a machine to create happiness because “sensations of happiness and sensations of misfortune are organically coupled in brain areas.” In passing, we learn from the specialist that “early relationships of the individual to life” produce, as in Israel, “the best students in the world,” and that it is also “preferable to live in Scandinavian countries,” where, as in Finland, only 1% of children are illiterate compared to 14% in France. After a quick trip to Ringkobing, a small town in Jutland on the west coast of Denmark, reputed to be the “happiest town in the world,” where he gathers insights from researcher Ruut Veenhoven, founder of the “Journal of Happiness Studies,” Stéphane Osmont joins economist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman in New York, awarded for uncovering the psychological dimension of economic decisions.

Finally, back in Paris where a final discussion takes place with philosopher Pascal Bruckner, our eternal aspirant, tired of this “scientific happiness,” gives himself over to the expert hands of a masseuse — or a masseur? — in a parlor “with fuchsia pink and pistachio green walls” to savor “the small pleasures of life,” meditate on the “madness of modern man,” and admit that “happiness is subjective.” Leaving us, dare we say, hanging! Psychoanalyst Catherine Millot had indeed once “interpreted” the author of this chronicle: “Charity begins at home.”

Stéphane Osmont, In Pursuit of Happiness, Éditions Albin Michel, 2009.