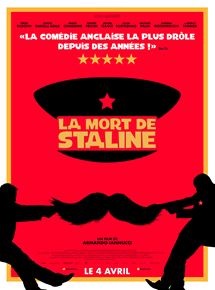

Inspired by real events, even if exaggerated, The Death of Stalin is a cruel, absurd, and exhilarating comedy.

On the night of March 2, 1953, a man is dying, devastated by a terrible stroke. This man, a dictator, tyrant, and torturer, is Joseph Stalin. And if every member of his inner circle — like Beria, Khrushchev, or even Malenkov — plays their cards right, the top position of General Secretary of the USSR is within reach.

In Stalin’s Soviet Union, fear was the foundation of power. Everyone, even at the very top of the state, was constantly on high alert, because in this realm of arbitrariness, a misplaced word, a misinterpreted grin, or a simple jealousy between neighbors was enough to send you, at best, to the gulag, or at worst, in front of the firing squad.

Then follows two days and two nights of negotiations, shifts in alliances, and devious maneuvers among the contenders for the head of the Kremlin. A fierce, often very funny massacre game, where witty remarks fly like bullets.

Armando Iannucci, master of political satire (like in the film In the Loop and the series Veep), understands this well: in his depiction of the agony of the “Little Father of the Peoples” and his lightning-fast succession war, the characters’ anxiety is, fittingly, ever-present.

But its intensity borders on the absurd. And it transforms everything — situations, dialogue, human beings — into caricature. Thus, into farce.

Everything seems unbelievable, yet everything (or nearly everything) is true in this adaptation of the well-documented graphic novel by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin. And when the screenplay takes a few liberties with historical reality, everything remains plausible.