Rodolphe Meyer is a young Doctor in Environmental Sciences and a graduate of the engineering school ESPCI. In 2015, while writing his thesis, he decided to create a science popularization channel on the YouTube platform called “Le Réveilleur.” His videos decode and analyze topics related to the environment with the goal of providing keys to understanding while fighting against misinformation.

– Very recently, Emmanuel Macron published a letter in many European media outlets. In it, he notably addresses the issue of the environment by proposing the creation of a Climate Bank. What do you think about the implementation of such a measure?

Yes, because we need investments for ecological transition. It is not only necessary but also politically feasible because there are other political advantages such as the creation of activities and jobs that will not be offshored or the reduction of our energy dependency (notably on fossil resource imports). Currently, the money created ex-nihilo is not directed at the European scale. It remains stuck on the secondary market and gets little to no entry into the real economy, which can create financial bubbles. Directing this monetary creation towards climate investment makes sense.

- Is it practically applicable for a group of countries with sometimes very different priorities?

It would be an economic investment plan at the European scale, and it’s perhaps one of the only topics where everyone could agree. Sure, there are still climate skeptics on the internet and sometimes in the political sphere, but broadly speaking, a consensus exists. These are shared values that can form the foundations of a European vision.

In my opinion, the biggest problem is not getting everyone to agree on the necessity of financing, but on what will be financed. And what will be financed will surely vary from one country to another. Nuclear, for example, is controversial among European countries. But France is not acting alone. There was a lot of talk in the fall about Sweden’s successful ecological transition, which has, like us, low-carbon electricity. But few people are aware that the country operates mainly on nuclear and hydropower, which cover 80% of electricity production compared to 10% for wind energy.

From an environmental point of view, nuclear is not absurd, but political tensions persist on this subject. In France, fighting climate change focuses on heat production and mobility, not on electricity production. We need to shut down the few coal plants we have left as soon as possible, but beyond that, the room for improvement is limited. If tomorrow we unlock the maximum amount of money to fight climate change, I don’t think it would be optimal to use that money to install photovoltaics or wind turbines, as the gain would be almost zero for the climate. This money could be better used for heat production, strengthening insulation, or evolving mobility. Conversely, a country like Poland, whose electricity production relies heavily on fossil resources, would have every interest in developing renewable electricity production means because it would directly reduce fossil resource consumption.

- Each country has specific climatic conditions. Is it wise to believe that only renewable energies will provide the solution?

Not all renewable energies are equal. Take hydropower, for instance. It’s an extremely interesting energy source but depends on topography. For Switzerland and Norway, it works very well, but for states like Belgium or the Netherlands, with little relief, it’s impossible. Photovoltaics are interesting for southern European countries, but in the North, it provides more electricity in the summer when we would need it more in the winter. Its interest is limited. On the electrical grid, at any given moment, it is necessary for distribution to equal production. If wind power is widely distributed but there’s no wind, electricity must still be produced for consumers. This requires compensating the intermittency of wind and solar with other production means. This explains why natural gas often accompanies the expansion of wind energy. The possibility of having a 100% renewable electricity mix when you don’t have a good hydropower base is a debated topic among experts…

We often forget that we use more energy for heat production and mobility than for electricity’s own uses. We must rethink building insulation and the arrangement of our cities. Train networks should also be revised. Renewable heat production methods (geothermal, heat pump, solar thermal…) are among the most interesting renewable energies, including in France. Yet, they are often ignored, in my opinion, for the wrong reasons. The obsession with electricity and intermittent renewable energies makes us overlook critical projects for our country’s energy transition.

Rodolphe Meyer

- On your channel “Le Réveilleur,” you have made several videos where you deconstruct the discourse of climate skeptics. Why this choice?

What motivated me to create this channel at first was the strong presence of misinformation on the internet, and for climate, it is even more pronounced in French than in English. In response to this discourse, I wanted to provide information as a reaction. I don’t think these are two different vocations. The videos where I dissect the words of climate skeptics force me to delve deeper into complexity. Ultimately, people learn more about the climate by watching these videos. Analyzing arguments is a credible way to teach, it could be done more often starting from this type of discourse to disentangle fact from fiction.

It also touches on something I missed a lot in my education. I went through prep classes and a major engineering school from which I graduated with a BAC +6. I then did a doctorate. I accumulated a lot of scientific knowledge, but I never had classes in epistemology (What is Science?). During my schooling, I was confronted with a lot of knowledge without being explained the scientific approach that makes these knowledge valuable. We too often forget that science begins with an admission of ignorance: we search because we do not know. This is what today touches on critical thinking, and more and more people are asking questions.

- Is misinformation a factor that prompted you to create the “Le Réveilleur” channel?

Yes. Overall, there is a lack of information on these issues but also misinformation, and the two are complementary. My mission as an engineer and specialist is to inform by showing the factual elements at our disposal. For societies to evolve, they must tell themselves stories, narratives. It is important to ensure that the narratives that prevail align with the facts. Otherwise, we risk expending energy on ineffective or even counterproductive actions. We must be attentive to the production of accurate information, but we must also fight against false information.

- Do you encounter climate-skeptic comments on your channel?

There are many climate-skeptic comments, sometimes very violent. From experience, climate skeptics are rarely convinced by arguments they have seen. If this were the case, it would be easier for me to offer a counterpoint. That was my naive stance at the beginning of the channel: just provide the scientific elements so everyone accepts the conclusions.

But many climate skeptics have a preconceived position and then seek elements to validate their viewpoint. This is called confirmation bias. I can respond to their arguments, but my response doesn’t change their position. The reasons that lead some to deny the anthropogenic origin of climate change are varied: economic, political, religious, psychological… etc.

Among those who produce climate-skeptic discourse, some are so subtle that I suspect intentional manipulation, and given the interests at stake, it would not be surprising. Others, on the contrary, make beginner mistakes and are simply victims of their ignorance and cognitive biases.

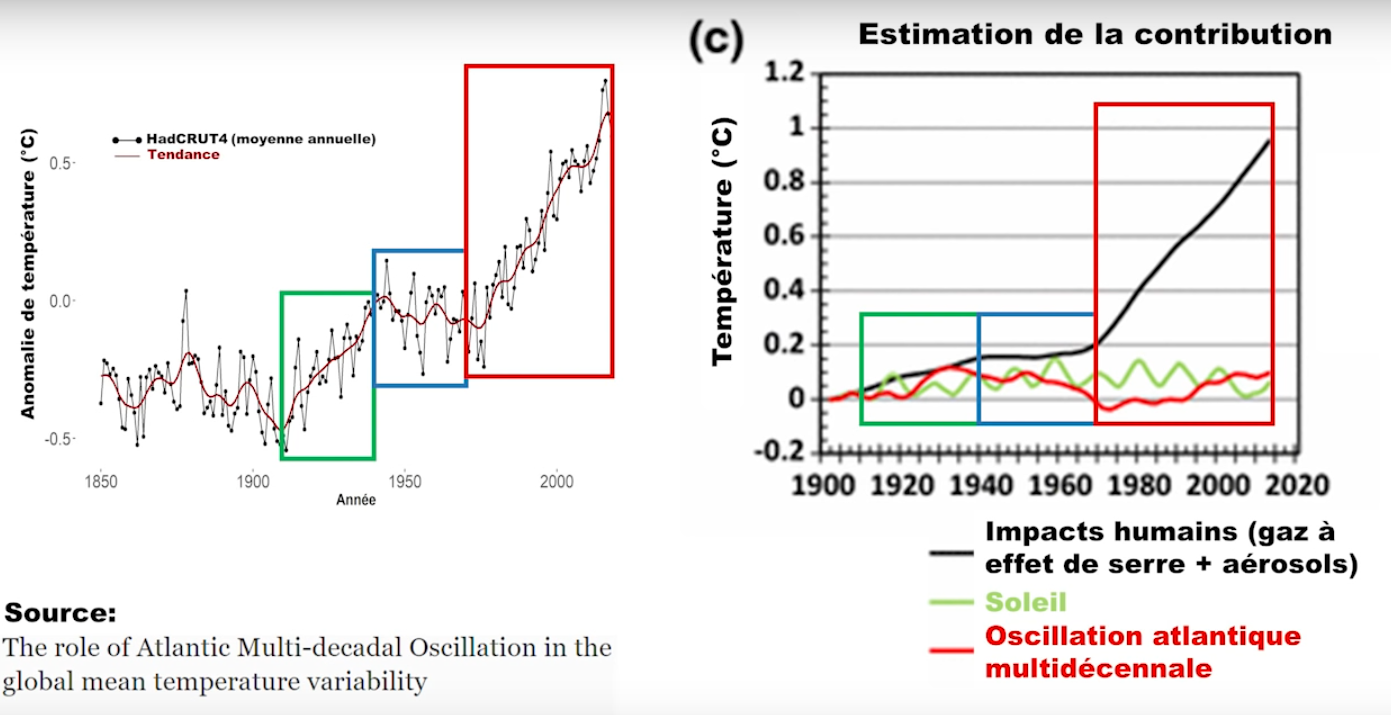

Rodolphe often uses scientific material to illustrate his points. Here, he highlights the fragility of a climate-skeptic argument.

- What are the steps in creating a video?

For the general format, I already have a list of themes. Unlike other video creators, I make a series of videos for each topic covered. I try to have an objective and synthetic approach, so I start by sifting through the literature. I use, for instance, reference reports like the IPCC report or scientific articles directly. It must take me 70 hours to write a script, which is about two full weeks of work. I have this script proofread by close friends and engineer friends who have an eye for detail. I also try to identify people with specific skills on a precise subject, often researchers or professors, for the technical foundation. Lastly, I film, edit and illustrate, which takes me another week.

- Is it difficult to popularize scientific knowledge?

Some may say I don’t popularize enough, and it’s true that shorter formats exist on YouTube. It all depends on whom you’re addressing. I think anyone with a minimum interest, making an effort, can follow my videos. I receive messages from high school students, even though they are not necessarily the target audience. In fact, I produce the content I would have liked to find. Many people have a scientific background but want to understand the state of affairs on these topics that are not always addressed with rigor.

My ability to synthesize and popularize these complex subjects is appreciated. Part of my audience directly finances my work, with no other return than the survival of my channel. Anyway, today, that’s where I feel useful, more than in a research laboratory.

- How do you integrate climate change into your worldview?

There will be many different impacts, some of which are already visible. Sea levels are rising, floods are more frequent in some areas, there are more fires. In fact, our societies are constrained on two fronts. Both in resources supply, as our current way of life relies on the extraction of non-renewable resources, and also from pollution. It’s a bit of a resource/pollution pincer that’s gradually squeezing society without us necessarily realizing it. A metaphor that comes to mind is a watermelon wrapped with rubber bands; after a certain number of bands, the watermelon explodes. It’s somewhat like that how I integrate these problems into my worldview. These are added pressures on society. We have to spend money to rebuild what’s been destroyed by a flood or to irrigate because of a lack of water. We will have bad harvests, and some parts of the world are starting to destabilize, causing population displacements. All these pressures eventually lead to a breaking point.

As our systems degrade, we will have less and less surplus and will have to choose what we lose. It will reduce our ability to evolve, adapt, and invest.

We often hear the discourse that it’s necessary to leave capitalism or change our political system. But the ecological problem is that we rely on stocks of non-renewable resources to produce things consumed by everyone that pollute. If we change the economic system without changing what we extract from nature and what we release into it, we will not solve our problem. It is essential to keep this in mind and only accept changes if they reduce our consumption of resources, especially fossil, and our polluting emissions.

People often tell me it’s human nature to accumulate, as if it were a kind of fatalism. It’s an idea I’m reluctant to accept, but even if it were true, I think we have far surpassed the stage where we were reducible to our nature. For centuries, we have been producing a culture that has nothing to do with our nature. Our political organization, property, money, nations, religions… none of this is natural; these are human constructions, fictions. Society’s evolution only occurs through the evolution of these fictions, of culture. I don’t see why we couldn’t produce a culture that accepts the existence of limits and adapts to them. Ultimately, the existence of limits seems more intuitive to me than today’s dominant culture, which would have us believe that infinite growth in a finite world is possible.

I think the ecological battle is fought here. Ideas need to evolve, the way our societies conceive themselves. It’s a cultural war, and there’s work to be done if we want to win it.