Sure,

To be clear, Nice Premium is neither in favor of nor against the project for the new Nice stadium. Everyone has their role. It is up to political decision-makers to take responsibility for making decisions by justifying them.

The majority presents its proposals, and the opposition opposes them if they do not identify with them. It’s that simple, democracy…

We want to be only a (modest) independent and participatory information tool. An independent and participatory press has only the duty to help public opinion position itself concerning the different stances by providing necessary and known information.

“Watchdogs” (‘watch-dogs’ as the Anglo-Saxon and American press claims)?

It may be an excessive ambition, but isn’t “lap dogs” a bit too compliant?

Simply, we think it useful to ask some questions to better understand this issue, solely for the sake of transparency and intellectual honesty. This is why our file (considerations and documents attached in Italian to underscore its origin) expresses no critical opinion but only presents observations and figures.

Simply, we think it useful to ask some questions to better understand this issue, solely for the sake of transparency and intellectual honesty. This is why our file (considerations and documents attached in Italian to underscore its origin) expresses no critical opinion but only presents observations and figures.

First consideration: The Stade du Ray is not a quality sports venue, and there is unanimity on this.

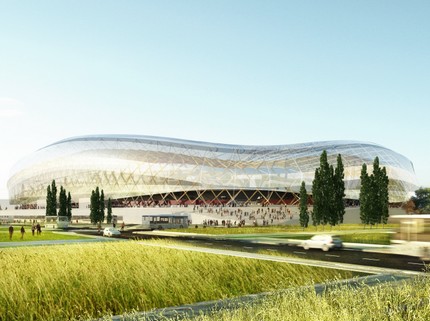

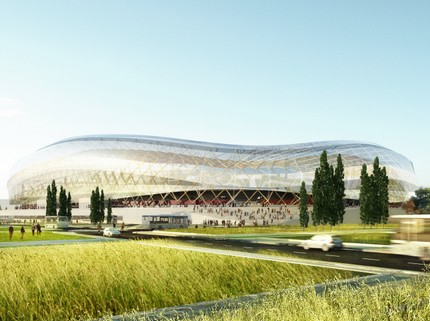

That the Olympic Stadium, on the contrary, will be is evident; the quality and modernity of this project are clear and recognized.

Second consideration: Analyzing the economic aspect and financial arrangement of the operation compared to another project with similar characteristics to see if we can do better and cheaper is always good and useful (this is called “best practices”).

Third consideration: That OGCN will become a leading club nationally or even internationally just because it will have such a beautiful “tool” seems risky, and asserting it would be pure propaganda.

Because when you hear that the average attendance will double or triple just for the new “Stadium,” you must ask what econometric forecasting rules are being applied! In short, blind optimism is not yet an exact science!

At best, one can say that this (the Stadium) is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Because the spectacle is on the field and will always depend on the quality of the players. Even if a modern and quality “tool” remains interesting from an economic potential point of view and will undoubtedly attract the interest of some investors, which seems to be the municipality’s strategy.

The local Socialist Party contested the choice of the municipal majority with arguments that can be summarized in three points:

1) A non-priority investment

2) An excessive cost that has significantly increased compared to previous projects (Peyrat 1 in 2001: €57 million; Peyrat 2: €83 million in 2006; Estrosi €157 million in 2008 and Estrosi Vinci Wilmotte €205 million excluding VAT in 2010)

3) Favorable contractual conditions for the concessionaires within the framework of the PPP (Public-Private Partnership).

But it is known that the role of the opposition is nevertheless only to oppose!

Nice-Premium, therefore, considered comparing the municipal project with another almost similar one currently under construction: the new Juventus Arena stadium, which will be inaugurated in the summer of 2011 and will be operational for the 2011-12 season.

This project (concession of the site by the Municipality of Turin to Juventus FC, a publicly listed company, for 90 years with construction costs and management benefits borne by the club) is comparable in size (+15%) to the future Nice venue (41,000 seats versus 35,000) as well as in commercial extension (34,000 m2 versus 29,000).

The technical and aesthetic features of this project certainly make it a high-quality stadium (see the box in Italian detailing them).

Can we therefore say that the two projects are comparable? Yes.

So, why talk about it? Quite simply because there are a few differences we would like to better understand the reasons for:

- Cost: The Juventus Arena is expected to cost €120 million (see financing in the box) compared to €205 million for the Nice Stadium. And this despite the fact that the previous Stadio delle Alpi had to be demolished, with the resulting additional costs.

- Financial aspect: The Municipality of Turin will bear no costs compared to the €8.3 million per year for 27 years that the Nice Municipality will have to pay. This is unusual for a PPP, which, by its legal structure, normally does not provide for this contribution.

As a result, the Nice municipality will reimburse the concessionaire for the incurred costs (8.3 x 27 = 224.1, which, considering the monetization, amounts to a figure close to the 205 million expected). Thus, the concessionaire will solely bear the financial costs on the invested capital and benefit from exploiting the Stadium (rent costs for OGC Nice should be €3/4 million per year) and commercial activities (net of management facility costs of at least €2 million per year).

Considering this, the Stadium does not seem to be the pinnacle of a “business model.”

The figures reported have been acquired from public sources. Nevertheless, the standard cost of a stadium is €1300 to €1500 per seat, and that of the commercial sector is €1000 to €1200 per m2.

We will limit ourselves to asking a simple question: Why ignore such an easy-to-verify example, certainly useful in information and comparison terms?

Isn’t the primary lesson for those in public responsibility “know to decide”?

Have we applied the advice-precept of our English friends: “to do the best to the possible”?

For Saint-Thomas (a perfectly legitimate role), see you on December 9 in Milan at the Football Show for the presentation of the Juventus Arena project during the “Solo la Juventus ha fatto gol?” colloquium: the Juventus Arena project will be presented by Jean-Claude Blanc, general manager of the Turin club and resident… of the French Riviera!

NICE STADIUM

NICE STADIUM

File

A public/private financial and legal arrangement.

To achieve this major sports facility, which is sorely lacking in France’s fifth city, a mission of legal and financial assistance has been entrusted to a consortium of consulting firms, lawyers, and study offices.

The financial solution for the realization of this project, in the interest of saving public finances, seems to be through a partnership with the private sector.

A multifunctional stadium of 30 to 40,000 seats in the heart of an eco-neighborhood.

During its April 23, 2009 session, the Bid Commission decided to entrust this mission to the group Pricewaterhousecoopers (mandate)/ TAJ Société d’Avocats/ ISC (Sporting and Cultural Engineering)/ Xavier Lauzeral, Architecture and Urbanism.

This group will assist the city in all its steps, from the notification of the market in May.

The chosen group (Vinci) is a specialist in complex operations integrating a Grand Stadium. It has participated in Europe’s most important references, such as New Wembley, Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium, London 2012 Olympic Stadium, and San Siro in Milan (?), but also in recent major French stadium projects, such as those in Lyon, Lille, Grenoble, or Le Mans.

The future contractor will have to meet the following requirements in their project:

Build a stadium to host UEFA and FIFA competitions up to the quarter, or even semi-finals, as well as matches between nations,

Choose the Saint-Isidore site, in the heart of the Eco-Valley, to serve as an example of integration and sustainable development, and integrate this sports complex into a new city district,

Introduce auxiliary facilities (museum, activities, shops, offices, restaurants…) to allow the site to live outside of sporting events, thus creating a real hub of life,

Facilitate access by all modes of transport: road (A8, RD 6202, and RD 6202bis), but also collective (extension East-West tram line, future LGV, international airport).

The timetable for the realization of the stadium

October 23, 2009: Municipal Council decision to ratify the Grand Stadium program and recourse to the Partnership Contract. Historic moment: Administrative cornerstone laid, irreversible decision,

October 26, 2009: Announcement of public tender notice for the Nice Grand Stadium operation,

End of 2009: Selection of groups authorized to participate in the consultation and dissemination of the Consultation File,

April and May 2010: Competitive Dialogue,

June 2010: Distribution to the groups of the Final Offer Request File,

September and October 2010: Submission of final offers by candidates and analysis of these offers,

November 2010: Designation of the winner and signing of the contract,

Early 2011: Application for building permit and studies,

Mid-2011: Start of construction,

Mid-2013: End of construction and commissioning.

The future Nice Stadium

Nice Stadium, a stadium in the heart of the Eco-valley.

It proposes a true model of eco-design and eco-construction with the implementation of innovative technologies that will make Nice Stadium one of the world’s first Eco-Stadiums.

This project includes:

- The multifunctional stadium of 35,000 seats dedicated to football, allowing the practice of rugby at the highest level as well as the hosting of seminars, concerts, and other major events.

-

Entirely sheltered stands, comfortable boxes and lounges, large walkways, retractable stands at the North and South allowing for great versatility and proximity of spectators during football or rugby games.

-

The national sports museum will present exhibitions over 3,000m2 distributed across multiple levels.

-

A commercial, services, and office program of 29,000m2 located at the stadium’s base.

-

1,450 underground parking spaces and the creation of a planted “park” of about 3 hectares on the surface.

JUVENTUS ARENA

JUVENTUS ARENA

The Juventus Arena is a football stadium under construction in Turin, Piedmont, that will host the home games of Juventus Turin. The stadium will open for the 2011/2012 season and will have a capacity of 41,000 spectators. It is being built on the site of Juventus’ former stadium, the Stadio delle Alpi.

Construction and opening

Start of construction: March 1, 2009

Opening: 2011

Construction cost: €105 million, later increased to €120 million for additional commercial works

Owner: Juventus Football Club

Equipment: Natural Grass Surface

Capacity: 41,000 spectators

- Public-Private Partnership

The concession is a method for realizing, financing, and managing public interest services and infrastructure.

Private participation is expressed through a range of public/private partnership modalities (“public-private partnership” PPP).

Between commercial enterprises operating in a strictly private law framework and pure public management lie hybrid and intermediate forms reflecting various levels of risk and responsibility sharing between the public and private sectors.

The concession is thus a mode of this public-private partnership (PPP).

The concession is a key element of project arrangements such as BOT (Build-on-Trade).

The concession system relates to the French public law tradition, such as public works contracts, supply or service contracts, public service delegation, emphyteutic lease, management or leasing or administrative contracts with diverse performance objectives.

Using the “Concession-BOT” technique aims to have a private company realize public infrastructure or equipment projects that would have been implemented and managed by public institutions or companies in the public sector.

The private company benefits from a concession to finance, construct, and ensure the project’s operation during the concession period.

At the end of the concession period, the project returns to the public concessionaire. The concession duration is determined based on the time necessary for the generated revenue to allow the company to repay its debt with a return on investment compensating its efforts and risks, including technology transfers it may have provided.

Fundamentally, concession-BOT arrangements result in paying for the service provided to the user rather than the taxpayer by substituting public management with private management under public control.